Lithuania has declared 2020 the year of Sugihara Chiune, a wartime Japanese diplomat who has been recognized by Holocaust memorial center Yad Vashem as Righteous Among Nations for his efforts to save the lives of Jews in Lithuania in 1940.

The year 2020 is the 120th anniversary of Sughihara Chiune’s birth, and the 80th anniversary of the actions he took as a Japanese diplomat to save as many people as he could before the Japanese government could stop him.

Monday, January 27, 2020, the 75th anniversary of the liberation of the Auschwitz-Birkenau extermination camp, would have been a perfect time for the Japanese government to call attention to Sugihara Chiune.

However, little has been done so far in Japan little to officially recognize the date, nor had there been much attention paid to the proclamation by Lithuania.

The Tokyo Holocaust Education Resource Center held an event in Tokyo, but Prime Minister Abe Shinzo did not attend. A week earlier in January, Abe had met Polish counterpart Mateusz Morawiecki, but talks focused on bilateral trade rather than the legacy of Auschwitz-Birkenau, which is located on what was once German-occupied Polish territory. On the anniversary on Monday, January 27, Abe made no remarks about Auschwitz.

However, Japan’s Ryoko Shimbun, a trade journal covering the tourism industry, did mark the anniversary with a Holocaust-themed story about plans to encourage tourism to Sugihara Chiune’s birthplace in rural Gifu Prefecture.

Writing 300 visas a day

Born in 1900, Sugihara Chiune joined the Japanese Foreign Ministry in 1919 and would eventually be posted to northeastern China as part of Japan’s colonial occupation government there. Sugihara became fluent in Russian during this time. Due to his language skills, Sugihara was appointed Japanese consul to Kaunas, Lithuania in November 1939, two months after the German and the Soviet Union invasions of Poland. In June 1940, the Soviet Union invaded the Baltic states, including Lithuania.

Because of the Soviet Union’s intention to annex Lithuania, Sugihara and other diplomats were ordered by the U.S.S.R. to leave the country by July 1940. As Sugihara was preparing to leave, a Jewish delegation in Kaunas approached him, requesting transit visas that would allow Jews in Lithuania to travel through Japan in hopes of reaching the Dutch colony of Curacao, which was said to require no entry visas.

Sugihara agreed. Sugihara stated in 1977 that soon his consulate was surrounded by up to 4,500 people. In defiance of his superiors at the Foreign Ministry, he wrote nearly 300 transit visas a day.

“I know it was a problem, but I couldn’t help it,” said Sugihara in the 1977 interview. “I told (Foreign Ministry staff in Tokyo) it was a matter of humanity. I didn’t care if I was axed. Someone else would have done the same thing if they were in my place. There was no other way.”

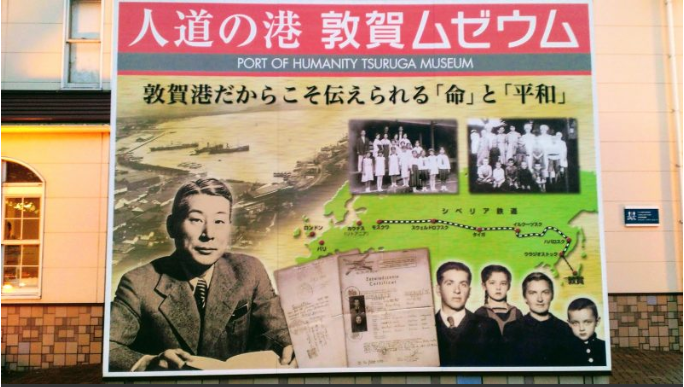

After receiving a transit visa for Japan, the Jewish refugees would then travel by rail to Vladivostok in the Russian Far East (it’s reported that Soviet leader Joseph Stalin personally approved the transit) or Busan, on the Korean Peninsula, where they would board a steamer to the Japan seaport of Tsuruga, before transiting on their way to whatever country that would take them.

By the time the Germans invaded the Baltic Republics in June 1941, Lithuania was home to about 250,000 Jewish people, including 15,000 refugees who had fled from Poland in 1939. By the end of the war, only 27,000 Jews would survive in Lithuania.

Getting help from Kobe’s Jewish community

With transit visas in hand, the eventual destination for Jewish refugees in Japan was the port of Kobe, in 1940 an important steamship hub with connections to China, Asia, and North America. First, many of the refugees would travel to Tsuruga, a small but important port on the Japan coast that was once regarded as offering the shortest route to Europe from Japan.

From Tsuruga, Jewish refugees traveled to Kobe, which was also home to a sizable foreign Jewish community known as JewCom. JewCom would help the refugees with visas and other paperwork with, it has been suggested, tacit support from Foreign Minister Matsuoka Yosuke, a powerful member of the Japanese government.

Many of the Jewish refugees were resettled in Shanghai, while others traveled to the United States, Argentina, Canada, and other destinations until the war in the Pacific commenced in December 1941.

It’s estimated that Sugihara’s exit visas saved between 2,200 and 6,000 people, although there is some dispute about the final number. For example, some refugees escaped using family visas that covered a larger number of people, while it’s likely other exit visas were forged. Sugihara’s surviving son Nobuki estimates the total was indeed 6,000.

Sugihara Nobuki has spent considerable time trying to dispel the myths that surround his father the diplomat. For example, while the quote “I may have to disobey my government, but if I do not, I will be disobeying God,” is commonly attributed to Sugihara, Nobuki says that it is inaccurate.

In a May 2019 interview with Times of Israel, Nobuki Sugihara said: “The truth is, he just took pity on these people and decided to do something.”

Sugihara spent the rest of the war as a consular official in various embassies in eastern Europe. After the war, he returned to Japan, and either quit or was fired from the Foreign Ministry in 1947. He spent his final working years in virtual exile, living away from his family in Moscow, where he worked for a Japanese trading company. He was recognized by Yad Vashem as Righteous Among the Nations in 1984, and died in 1986 in Kamakura, Japan.

Besides attempts to encourage more tourism to Sugihara’s birthplace in Gifu, other commemorative activities in 2020 include renovating and expanding the existing Tsuruga Port Museum to tell the story of Sugihara Chiune and increase tourism to the city.